The unique joy of sleeping in a shepherd’s hut bed

In our latest post we take you through how a shepherd’s hut bed provides the ideal sleep sanctuary. Master hutmaker, Richard Lee, follows on by telling the story of the history and heritage that goes into each bed that Plankbridge produces.

A good night’s rest is something we all aim for, and is so restorative. Read on and find out why hunkering down in a shepherd’s hut bed is a move towards a peaceful night.

The birth of the shepherd’s hut

In Victorian Britain sheep farming was big business. Many communities grew very wealthy on the back of the wool and lamb industry. Peppered among the pastures of these communities, particularly on the downland of Southern England, would often be shepherd’s huts, built so the shepherd could be close to his flock during lambing and to use as a base throughout the year.

Shepherds would depend on these small, wheeled huts to sleep, shelter from bad weather and store tools. The huts typically included a bed, a table, a stove and storage space. A modest setup. But one that provided a place of calm amid the hard work. These days, however, you don’t need a flock of sheep to enjoy a shepherd’s hut sleep.

Slip into something more comfortable…

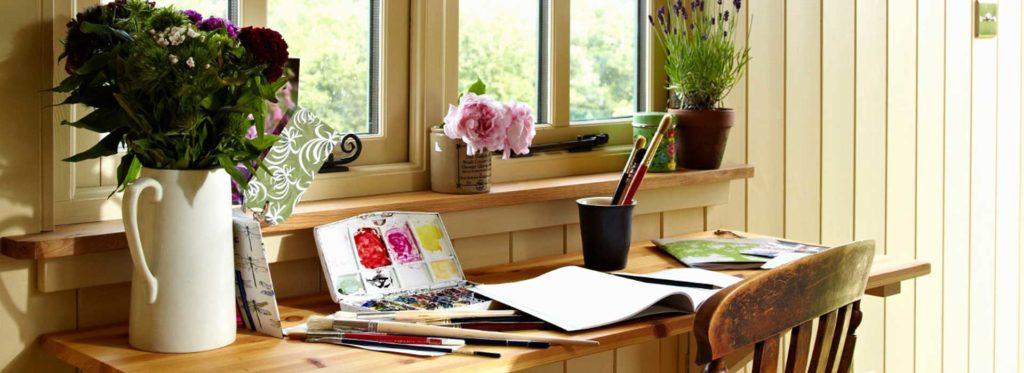

The Victorian sheep farming industry may have been a lot less productive if the shepherds had access to en-suite baths and luxurious double beds. At Plankbridge the idea of the shepherd’s hut as a place of refuge remains central. But by marrying the quintessential architecture of the Victorian design with modern interiors, we create forward-thinking living spaces – where time-honoured heritage meets modern style.

There’s an intrinsic romance about sleeping outside in a cosy shepherd’s hut. It may just be a short hop from your back door, but a world away from the daytime stresses and nocturnal temptations of your home. A space that’s peaceful. A space that’s uniquely yours. And a space that takes you a little closer to the soothing, soporific hand of nature.

Fall asleep gazing at the stars

You don’t need to be told that it feels good to get close to nature. But even fifteen minutes spent looking at nature promotes psychological rejuvenation. And the sounds of nature have been proven to decrease cortisol levels. That bodes well for a relaxing night’s sleep.

With your choice of Snug, Cabin or Custom Made Hut, a Plankbridge shepherd’s hut gives you the best seat in the house for observing nature, while offering the tantalising opportunity to fall asleep while gazing up at the night sky through one of our our curved roof lights, and fantastic bit of timber engineering in oak.

But it’s not just the stars that make a shepherd’s hut special. It’s the sound of the rain doing a gentle dance on your window. It’s watching the trees as they change with the seasons. It’s the birdsong as you enjoy a few pages of your book with a morning coffee.

Whatever the weather…

Being closer to nature means being closer to the weather – and it won’t always be the proverbial red sky at night. Made to exacting standards by experienced craftsmen, Plankbridge shepherd’s huts make light of the heavy weather. It’s why they come with a twenty year structural guarantee. Weatherproof and fully insulated with Thermafleece British sheeps wool, they are a joy to hunker down in, whatever the weather.

Luxurious comfort, intelligent space

The shepherd’s hut beds of old would have been simple affairs. Perhaps hessian or canvas stuffed with horsehair. Luckily your shepherd’s hut bed will provide a far more luxurious experience. We fit Italian Orthosoft mattresses as standard. Exceptionally comfy, yet easy to make up with the sheets.

Ingenious use of space is a hallmark of a Plankbridge shepherd’s hut. We typically fit fixed doubles in our shepherd’s huts, with a sloping headboard so you can sit up to read. However you may prefer a day bed, a sofa bed or even bunks. Your hut, your way.

From master hutmaker Richard Lee – the story of the history and heritage of the shepherd’s hut bed.

‘I’ve made a lot of beds for our huts over the years, but it took a while for the idea to kick in. My first workshop was shared with two other graduates from Hooke Park College, an extraordinary monastery dedicated to woodwork based in misty woodlands in West Dorset, not far from Beaminster.

It was a fantastic place created by international furniture designer maker John Makepeace. I did the brilliant summer short course, followed by two one year stints. The final year linked up with Bournemouth University at which point it felt, to me, to be sadly holding hands with conventional education establishments. The inherent eccentricities I had been attracted to arguably became diluted. The site ended up being a centre for the Architects Association and is thriving now. But in the pioneer days, at its core, Hooke Park was about nurturing entrepreneurs in wood; training and inspiring us to go out into the World and establish energetic businesses using a renewable resource.

Fellow graduates Matthew Lewis, Tom Harding and I found a workshop in converted chicken sheds near Halstock, on the Dorset / Somerset border, just the other side of the Beaminster hills.

I concentrated back then on a rustic style of chairmaking, inspired by the work of Dan Mack in the USA. He also made some amazing beds, very sculptural, and his work led me to research the 19th century rustic traditions of the Adirondack mountains in New York state. There was a trend made popular in magazines like Country Living for a style of what is now known as ‘cottage core’.

Tom and Matthew soon became really busy making wooden accessories for design-led interior shops with smart London addresses. I drifted around trying various in-roads into the market, from the early rustic chairs to Adirondack garden seats which did quite well. All the while I was looking for that golden ball to bounce by, to find the right product or design that hit the spot and had enough weight to base a sound business upon. I had no idea what a shepherd’s hut was in those days. A few craft galleries, including a decent sized one in Salisbury, would often suggest I made a bed design. ‘We could sell those’ they would say, but it never came to anything. I don’t know why but I didn’t follow through and make something to try in the gallery, despite the fact that every time I saw the gallery owner she would ask ‘Made me a bed yet?’ I’m sure they were right: a double bed with a headboard in the rustic style I was immersed in at the time would have looked great and filled a niche.

Making my first bed

The first bed I ever made was at my first job when I was eighteen years old. I found a position on a private 120 acre lake on the Cotswold Water Park, just south of Cirencester. The owners had renovated an old mobile home for me and positioned it with a fantastic view looking across the lake. The bed was way too low to take advantage of the large picture window so I built a much taller bed with storage cupboards beneath. I would have utilised whatever wood I could find; we were building Finnish log cabins there at the time, amongst other things, so there would have been plenty of offcuts to hand. I had only really played at wood turning before that, so the bed structure would have been pretty basic and freeform but it did the job.

Starting Plankbridge

I moved here to the old Dorset watercress beds in 1998, where Jane and I established Plankbridge, and where we still live. I turned the packing shed end of the building into a workshop, and it later evolved into our kitchen. Although fairly small before building works extended it, it lent itself to a workshop well. For thirty years the place had been a laboratory ‘down south’ for the Lake District based Freshwater Biological Association, so the space was well equipped for a small business. They ran experiments and monitored the borehole water in the numerous chalk springs on the site. For a year or so I also worked for another Hooke graduate, the renowned furniture and kitchen designer Simon Thomas Pirie. We made chairs and tables but, I don’t recall, any beds at all. Strange really, as it’s the piece of furniture that we all use the most and almost ten years into my self-employed career and I still hadn’t got into beds.

After working on a few quirky projects out of my tiny workshop I did a sculptural set of stairs for a barn conversion near Sherborne. Old friends of Jane’s, the owners had established a successful iron bed company. One day Billy asked me to do a wooden bed as part of their range. I made a stout ash frame with a tall headboard, with iron bars for the rails. The bed base was fitted to their established method, so I simply had to make the head end and foot end with forged brackets for their side rails to bolt on. It was a really good thing to produce. I could make two or three a week as required, hand apply a neutral wax finish and load them into my trailer and every Friday drive them up to their workshops on a farm near Wincanton. I was witnessing their business grow, and it was exciting to be a part of it. One week a new powder coating line would go in, the next a new range of offices would be converted from redundant sheds. There were iron beds everywhere and it was fascinating to see their production process evolve.

One day Billy and I were chatting. I had been fitting some complex cupboards and other bits into a motor home he was prototyping, the curved shapes being a big challenge to fit to. Ever the innovative dreamer he was always looking for ideas, as was I. The idea of that summer was a high-end motor home. ‘You need to make something with plenty of air in it’ he said, thoughtfully, ‘there’s too much labour in just a cupboard or a kitchen, find something bigger. That’s what you need.’ I suppose that was the thinking behind his vast motor home, which ultimately was way too complex with wires, pipes and gizmos to be viable.

It was around this time that we found a shepherd’s hut sitting lonely and lost on a trackway near the house.

The original shepherd’s hut bed

At its most basic a shepherd’s hut provided much needed shelter for the Victorian shepherd as he tended his flock on the downs of Southern England. It was effectively a bed with a cover around it. I imagine the shepherd would have found so much comfort from the simple bed, a mattress of horsehair and some thick blankets for warmth. I can really picture the evocative scene; the comfort of the small pot-belly stove, the worn floor, the aged pine walls patinated by rural life and lanoline hands. I love to see the wear marks on old huts and in such places as watermills and workshops where daily use has left behind rounded corners polished by working hands. The dished shape to an ancient stone doorstep on houses and barns, worn down by a thousand footsteps always surprises me. Perhaps hobnail boots added extra abrasion.

My great grandfather, who lost a leg in the trenches, had a Windsor chair where he apparently spent much of his time. The Elm seat is rubbed thin on the left side by his wooden leg. A bed has the same sense of visual history, the mattresses will come and go of course but the frame takes on the energy of all those that pass through it. There could be more to it than that.

Someone once told me that the concept of ghosts is actually the energy of past lives absorbed into the woodwork of old buildings, and I love that. The thought that living things give off an electrical energy much the same as a light bulb, the energy of which has to go somewhere. Maybe human energy is absorbed into the fabric of an old building, and into the wooden frame of an old bed.

A Plankbridge bed

Most of our shepherd’s hut beds are fixed singles or doubles, avoiding the gimmickry of wall beds that hide away in caravans or motor homes. I much prefer to see an inviting bed all made up and ready to go. To be able to jump right in, rather than pulling on straps and levers at bedtime is much more appealing. The old ways are the best. However we are exploring the more complex wall bed designs again, and if we can do it in the right subtle way we will.

A shepherd’s hut provides a separate space to sleep, work and play. What more can you need? We have delivered some fairly basic huts with just a bed and stove into some incredibly remote and interesting locations. I remember delivering one into a fenced enclosure in private woodland surrounded by Australian wallabies – in the home counties of England. Another hut was mounted on rubber wheels for easy relocation around a country estate in the Midlands; he commissioned what he thoughtfully called a ‘marriage saver.’ A comfy double bed, a warm stove, an open mind and an ever-changing view.’