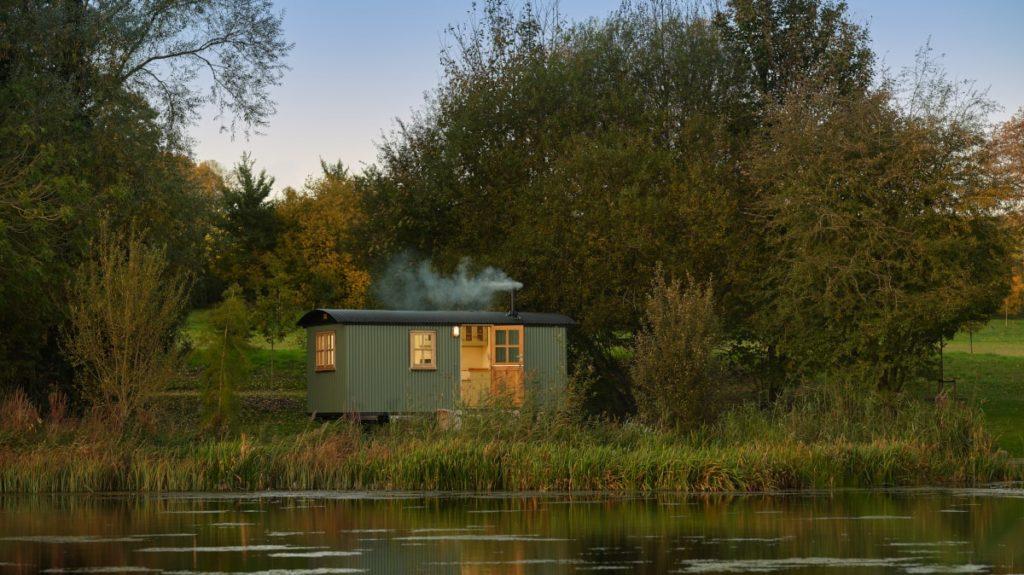

Start with why, in the words of one particular inspirational speaker. We know what we do, and how we do it. The question should aways be; why do we do it? I have retreated to the shepherd’s hut; the stable door is closed to keep out the hubbub of the distant neighbour’s Saturday afternoon. The side window is open, allowing in only the call of the contented wood pigeon and the familiar birdsong.

I’m thinking of my first job, fresh from school and into my first few days working on a lake in the Cotswolds. A letter had led me there, that I had written to the author ‘B.B’. I had enjoyed his writing, and admired his black and white scraper board illustrations, for years and had corresponded with him for a short while. His children’s adventure classic Brendon Chase was particularly inspirational. In one letter to him, and not sure of my future path, I rounded off by asking, ‘what would you do if you were me?’ In a reply based on my apparent interests and scrawled in an old man’s hand on headed blue notepaper, which I still have, he said ‘heaven protect you from working indoors’ and to ‘try Bibury trout farm, they may have something for you.’ I fired off a letter to them, and waited.

One evening the telephone rang and, unusually as it was never for me, I answered. A distant voice reeled off the details of a nature reserve lake, a former gravel pit South of Cirencester, not far from Bibury. He and his wife needed a helping hand for children’s pirate parties, boat tours in an Edwardian launch, building log houses, decks and bridges, a small trout farm, Christmas trees to grow and harvest, wallabies to look after too. Would I be interested? I said yes.

Fresh from school and having not done much real work, it came as quite a shock. For the first few days my task was to mow between rows of young trees with a Hayter Osprey mower. By the end of day one my hands were locked shut, rigid from the vibrations of the unfamiliar, powerful machine. My digs, where I collapsed that night, were in a mobile home on a lake peninsula. It had been recently stripped out, well renovated and lined in tongue and groove. A similar interior, I can see now, to the larger Cabin version of our shepherd’s huts we produce today. I soon made a taller wooden bed so I could see out across the lake from the picture window. I had a Jotul stove, a small kitchen and a decent shower. It was to become my home for a few years.

I was allocated one of the owners’ Belgian shepherd dogs and I suppose Girla and I had the security brief. But I slept soundly then, as now, and so did she. And so began a life which knew nothing of working hours or set breaks. We just did things, project after project which instilled a strong work ethic and an eye for what’s possible. The trout cages went after a while, along with my tolerance for intensive farming of any kind. We pushed the floating fish pens to the end of the lake with the boat and dismantled them for a Scotsman to take away by lorry. The spring fed lake thanked us for it, the water returning to gin clear, and it later became a Site of Special Scientific Interest.

Slightly wide eyed to begin with, it was a life of working in a pair, as a team and often alone. Of learning that if we want to lay a pipe across the lake we make a raft. If we want to drive in huge Douglas fir piles to build a bridge, we find a way. There is always a way. I will long remember the seemingly impossible task of diving down to cut off redundant metal scaffold tubes, rammed into the bed of the lake, by hand with a hacksaw. It is why I cannot bear intransigence now. I learned so much from my boss then, they were very good times and he worked me hard. Firm but fair, he would say. One morning I didn’t wake at the agreed time for some project that we were on, so I was awoken by the strange sensation of my small home being rocked by the bucket of the digger as he tracked past.

I would take groups out by boat on a tour of the one hundred acre lake, smiling at their enthusiastic questions such as ’you must need a very big liner for this pond.’ I would work behind the scenes as visiting children enjoyed the weekly pirate birthday parties on one of the islands. I would take the provisions across by boat to set up the birthday tea, and without fail the carefully crafted pirate ship cake would fall in half, shipwrecked until I made a hasty but invisible repair with chocolate fingers.

The log houses, real ones imported from Finland and swiftly erected by two huge Finnish house builders, were by far the biggest projects we did. I learned so much, from driving dumper trucks and completing groundworks through to laying the floors under the watchful eye of Kim and Timmo. I remember being awestruck as these ever smiling Finnish men would raise the log walls and cut window openings with their chainsaws. Projects took us, and various hired in helpers, to the Wye valley, to Surrey and later to build a school with logs on the outskirts of Bath. By then I had started to drift, enrolling on a land agents course at the nearby Royal Agricultural College where after a year, whilst I did learn many new things, I couldn’t find my feet at all. My time at the lake, and the college, was drawing to a close. The lake morphed into a corporate entertainment venue before becoming the exclusive and wonderful place for log house holidays it is today. I was to head off to New Zealand before returning home to embark on a radical timber, design and wood working course at Hooke Park college in West Dorset.

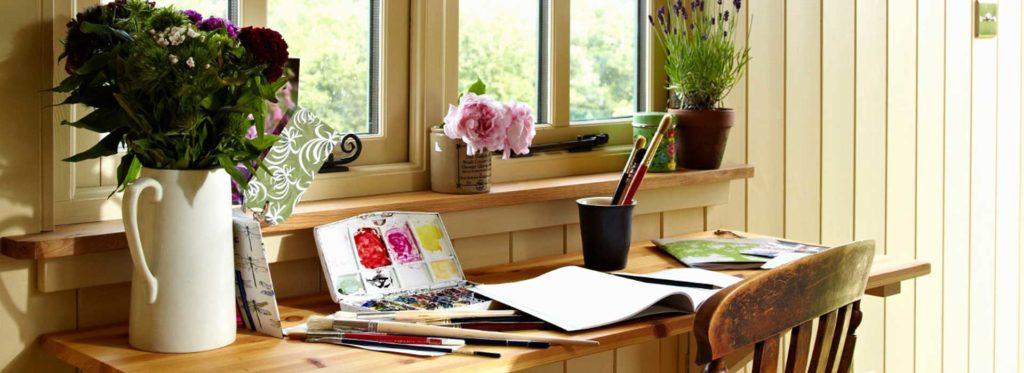

Why do we do what we do? It is the magic moments that I think of now, such as when the Irish carpenter played his flute as the close knit team gathered as work on one of the houses ended for the day. Or those times when things were just right and I was so lost in making something that my hands were creating as if under a spell and my heart would sing. I can see myself in my armchair by that Jotul stove in Winter, warming up after a long day out building a deck, clearing the snow from the boards before I could start work. That’s when I would dream of things to come, of how making things would be at the core of what I would do and how I longed to always be living by water. Of course, I had no idea then what it would be that I would decide to make. I wanted it to be my idea, not to take the lazy route of copying and riding on someone else’s endeavours as many have done since. One mantra that has stayed with me from those formative days at the lake is ‘Always thinking ahead, always things to be done.’ As I rest here in my shepherd’s hut now, I can see clearly how the seeds were sown.

Musings from The Pondside | Part I

Musings from The Pondside | Part II

Musings from The Pondside | Part IV