A series of pieces of writing from Plankbridge founder Richard Lee, where he considers things as diverse as design, conservation and heritage.

There is a humble old gate, known as a Dorset rod gate, which goes largely unnoticed, sandwiched as it is between relatively modern houses a few yards from Dorchester’s 18th century Grey’s Bridge, on the approach into the county town.

At first glance it seems to mark a ransom plot; perhaps retained as a future pension payout for the owner to sell for essential access to developers. But there is only the millstream and floodplain beyond. Or maybe it simply yields occasional access behind the houses and stream; although it doesn’t seem to have been opened for years.

Made of oak, with perfectly spaced horizontal iron bars, there are many of these Dorset rod gates around the county, and most were crafted at a workshop in West Dorset by H. Leaf and Sons of Powerstock. This is printed on distinctive yet oh-so-simple Bakelite makers plates, and many date back sixty years or more. The National Trust are recreating many of these gates, and they point out that they will last four or five times longer than modern pressure treated softwood gates.

One of the local legends amongst woodworkers is of old Mr Leaf hand finishing the oak with a piece of broken glass, using the sharp edge as a cabinet scraper and feeling by hand for the high spots and rough patches as his eyesight failed. This has always struck a chord, and I have a longstanding image of the old boy in his tweed jacket carefully feeling his way around the oak frame, scraping delicate shavings with just the right shard of glass.

The old gate is fading now, and is backlit by the gone-to-seed wilderness beyond. One day it will no doubt disappear, for whatever reason, and that is sad. The design is an example of the perfect form following its all important function. The originals have clever hinges, the top and bottom horizontal oak rails run through to take metal pins which forms the hinge on stout oak or chestnut gateposts. I notice that modern recreations often forego that for more familiar metal strap hinges.

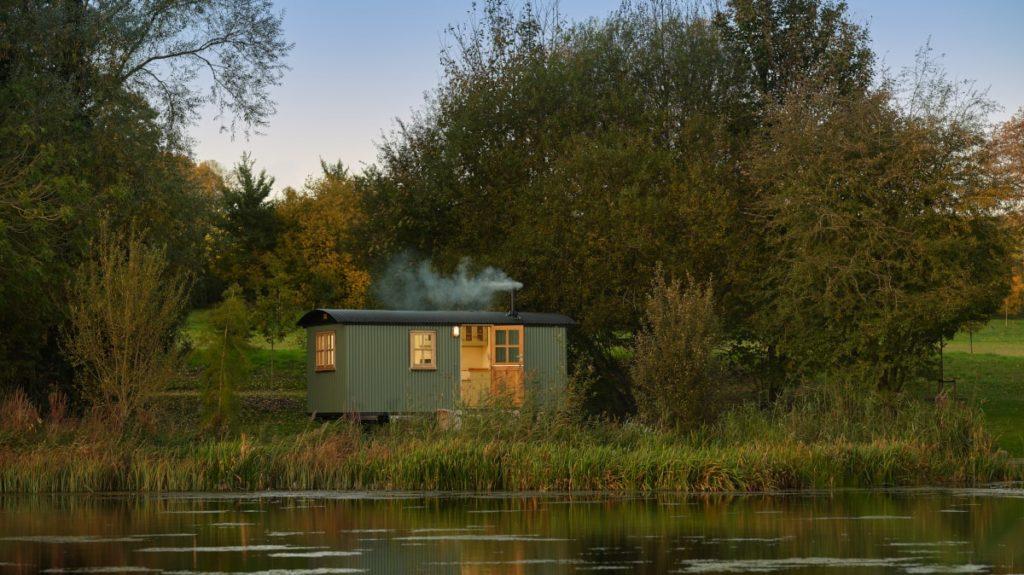

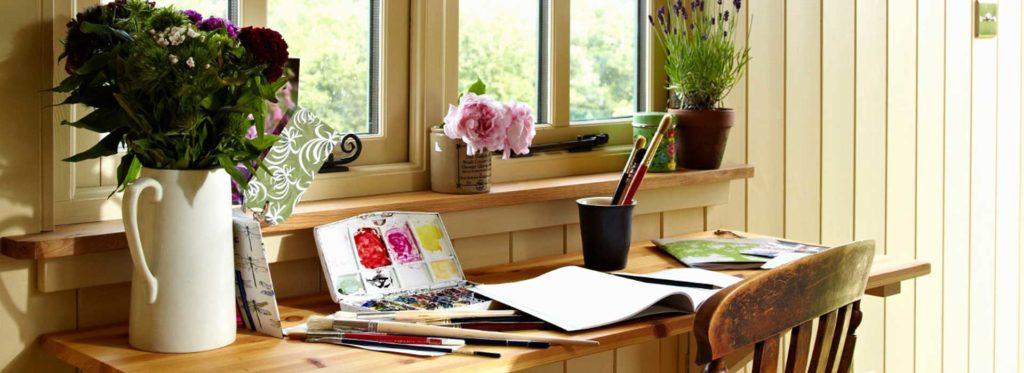

It is from these things that we pick up on in much of the detailing in our shepherd’s huts and cabin designs. The metal rods for our steps which, on our chestnut stringers, run through a copper sleeve to keep the iron from reacting with the tannin-rich timber. These are a nod to the Dorset gate, and our oak shutters take a leaf out of the same book. Our new leather door straps, crafted by a local master saddler, are inspired by details on ploughing harness. The ladders to our bunk beds are increasingly influenced by what I call ‘Granny’s steps’ from the 1950’s. Newly qualified apprentice Tom has been given the brief to carry the wonderful detailing of those utilitarian step ladders into our contemporary bunk ladders. There is a subtle perfect sweep to the corners of the treads, a visual bead runs the length of the stiles, and thin metal rods have recessed nuts to the sides, pulling the structure up tight whilst leaving no protruding metal to snag clothes. The result of years of evolution, such a perfect design was definitely not created in one sitting at a drawing board. It is very satisfying to evolve our designs in a similar way.

Does it matter when these things are gone? Not, I suppose, if we make an effort to notice them now and carry them through, to learn from them and the hands and eye of the craftspeople who went before.

Not far from this gate, on the London Road approach into town, was a heating oil depot. Tucked in behind the fence was an old railway Lamp Hut, unremarkable and certainly unloved. Corrugated clad with a curved metal roof it looked much like a shepherd’s hut without its wheels. A few telephone calls and a bit of persistence and the Lamp Hut was ours if we cleared it away. It sat in our workshop while I absorbed the proportions and structure. The heavy angle iron framework was bolted together with metal flitch plates and it was certainly built to last. Lamp Huts stood by the steam railway lines near the stations, to store flammables a safe distance away. Quite how it ended up where it did is anyone’s guess. The modular corrugated iron houses and tin tabernacles that were made in England and shipped flatpack around the World to the colonial empire were made in a similar way, probably in the same factories.

The oil depot has now gone, recently razed to the ground and a new retirement development of flats is underway. The Lamp Hut lives on, undoubtably saved from the demolition crew who cleared the site. Spotted in the corner of the workshop by TV presenter Kate Humble, we converted it into a kitchen and shower room to sit next to a Plankbridge shepherd’s hut at her ‘Humble by Nature’ smallholding school in Monmouthshire.

My office is in a 1920’s Bournemouth tram, number 113 and made by the Brush Motor Company in Loughborough. I find it inspiring everyday to witness the detailing and craftsmanship inside, from the reeded window frames to the perfect curve of the glass. Much of the interior is Burmese teak, which shocks and amazes me now as it was extracted from the remote jungle hills by trained elephants, the story of which is chronicled in ‘Elephant Bill’, by J. H. Williams. I have a photograph of our actual tram, 113, outside the Lansdown Hotel in Bournemouth in the early 20’s. I can only wonder at the stories it could tell. I don’t have it for restoration, it is for inspiration. It is there, trapped in its faded glory, to inspire and remind me how things can and should be made. A customer with a good eye and a great way with words once told me that ‘the angels will fall from the sky’ if I attempted restoration, the patina of so many years being intrinsic to its magic. I once had a dilapidated Morris Traveller for the same reason; the English ash framework and Alec Issigonis’ beautiful hand-drawn body curves offering inspiration in much the same way.

All these ripples from the past ebb and flow around us, making the waves upon which we sail into the future.

Musings from The Pondside | Part I

Musings from The Pondside | Part II

Musings from The Pondside | Part III